Steering light with sound in photonic chips

Scientists have discovered a way of harnessing sound waves to steer light, which could pave the way for miniaturised atomic clocks and GPS-independent navigation

Researchers from the University of Twente (UT) have reported a technique for steering light with sound waves, offering a powerful new tool to expand the scope and performance of photonic chips. This development could open up the possibility of making atomic clocks small enough to fit in satellites and drones, helping them navigate without GPS.

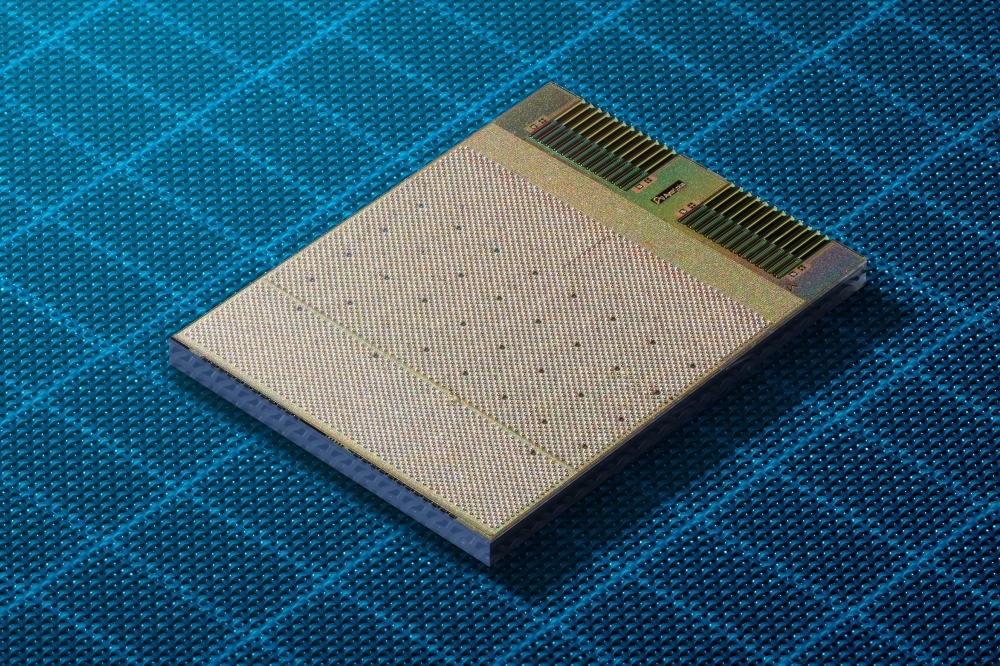

Detailed in the latest issue of Science Advances, the scientists have moulded the precision and versatility of a physical phenomenon called stimulated Brillouin scattering (SBS) into a form that’s ready for mass manufacturing. The team says that, with SBS added to their toolkit, engineers will be able to incorporate sub-Hz-linewidth lasers, ultra-selective filters, and many other components with unparalleled performance into their PICs.

“Integrated Brillouin photonics is very fertile ground, both scientifically and commercially, and our work takes it from the lab to the fab,” says David Marpaung, a professor and the chairholder of the Nonlinear Nanophotonics group at UT.

For the telecom industry, Brillouin scattering is usually a nuisance. In an optical fibre, the interaction of light with the glass creates periodic changes in the medium’s density and refractive index, scattering the light and limiting the power that can be transferred from A to B.

But Brillouin scattering can also be useful. By carefully controlling the positive feedback loop between light waves passing through a medium and the sound waves (called phonons) that are generated in the material’s crystal lattice due to its interaction with light, a new way of transporting and processing information emerges.

“After electrons in electronics and photons in integrated photonics, think of the phonon-mediated interactions as a third way to shape, redirect, or process signals,” Marpaung explains.

Until recently, however, leveraging SBS hasn’t been practical. “There have been many proof-of-concept demonstrations, but, for a variety of reasons, these face critical challenges in terms of practical deployment and scalability,” says Kaixuan Ye, a PhD student in Marpaung’s group and first author of the Science Advances paper.

Another major roadblock has been an intrinsic property of acoustic waves. Much like ripples spreading across the surface of the sea, acoustic waves tend to propagate in all directions, dispersing their energy. Marpaung, Ye and colleagues found that in the optical material lithium niobate, the acoustic waves can be steered by the direction of light, essentially taming it for insertion into integrated photonics technology.

To provide a taste of the new functionality that’s available, Marpaung’s group collaborated with the research group of Cheng Wang of the City University of Hong Kong. They fabricated an on-chip Brillouin amplifier and laser in the TFLN platform – two key components in any PIC. The team also created a more intricate component, a multifunctional Brillouin microwave photonic processor capable of filtering an incoming signal.

According to the team, these demonstrations open the door to real-world applications, which Marpaung has started to explore. “SBS can drastically reduce the dimensions of atomic clocks, since SBS allows for miniaturisation of the ultra-precise and stable lasers required by these devices. Chip-scale lasers will enable cost-effective integration of atomic clocks in satellites and unmanned aerial vehicles (drones). Thanks to precise on-board timekeeping, these devices wouldn’t have to rely on GPS for navigation,” he explains.

“Our work also allows for ultra-precise filtering of unwanted signals. Integration with high-speed modulators will lead to higher performance, smaller size and lower cost. These filters can be used for mitigation of unwanted interference and jamming, which is important for 6G radios and GPS/navigation.”