Trapped atoms act as a transistor for photons

Researchers say they have observed ultra-cooled atoms behaving like a gate for light on a nanophotonic circuit, either blocking photons or allowing them through, depending on the state the atoms are in

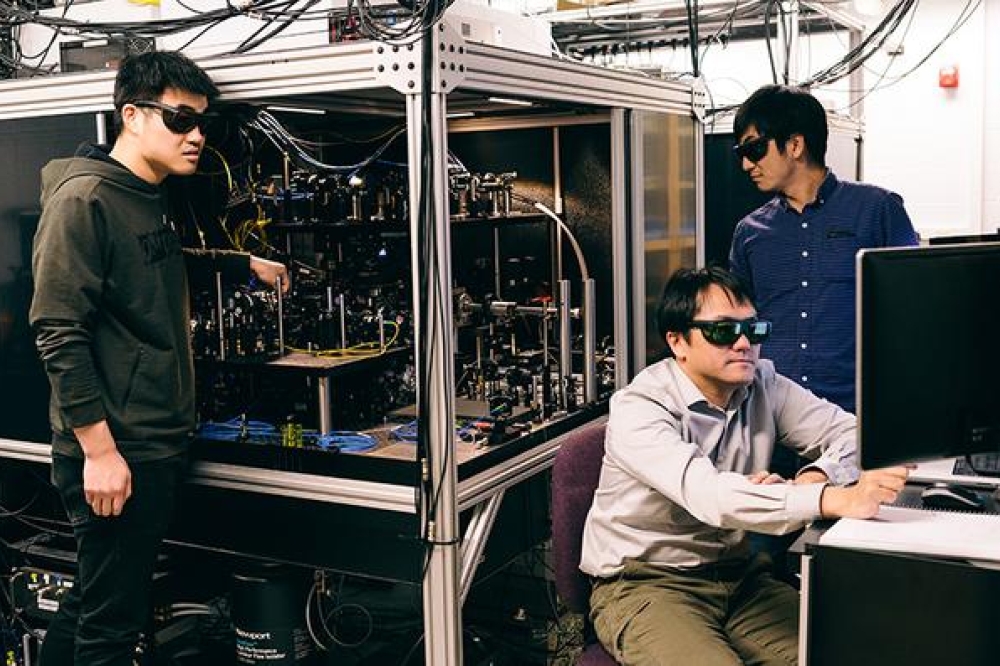

Researchers at Purdue University have reportedly trapped alkali atoms (cesium) on an integrated photonic circuit, which behaves like a transistor for photons similar to electronic transistors. The scientists say that these trapped atoms demonstrate the potential to build a quantum network based on cold-atom integrated nanophotonic circuits. The team, led by Chen-Lung Hung, associate professor of physics and astronomy at the Purdue University College of Science, published their discovery in the American Physical Society’s Physical Review X.

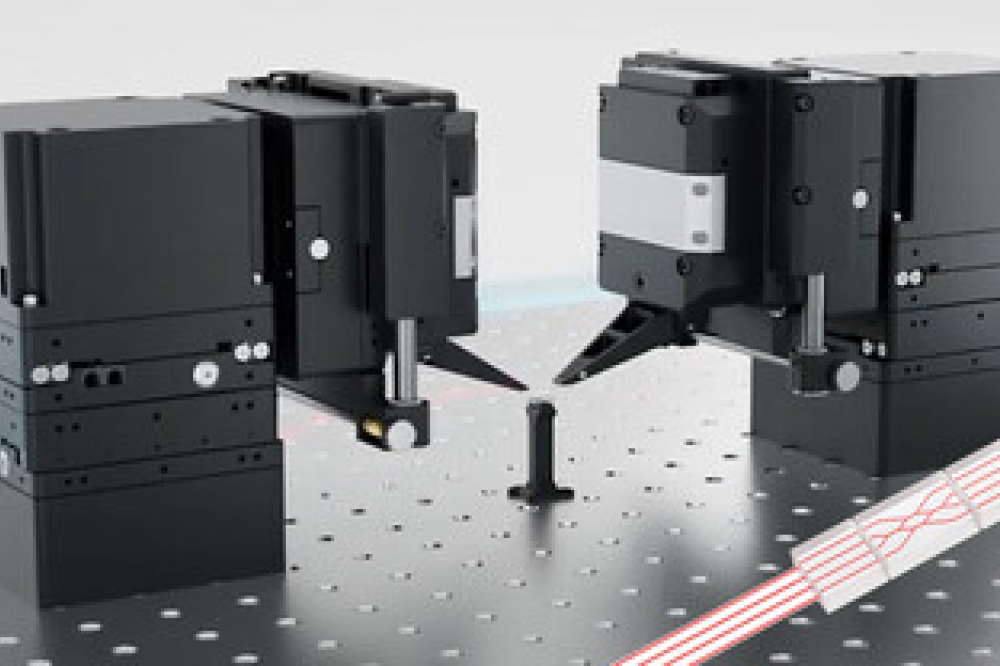

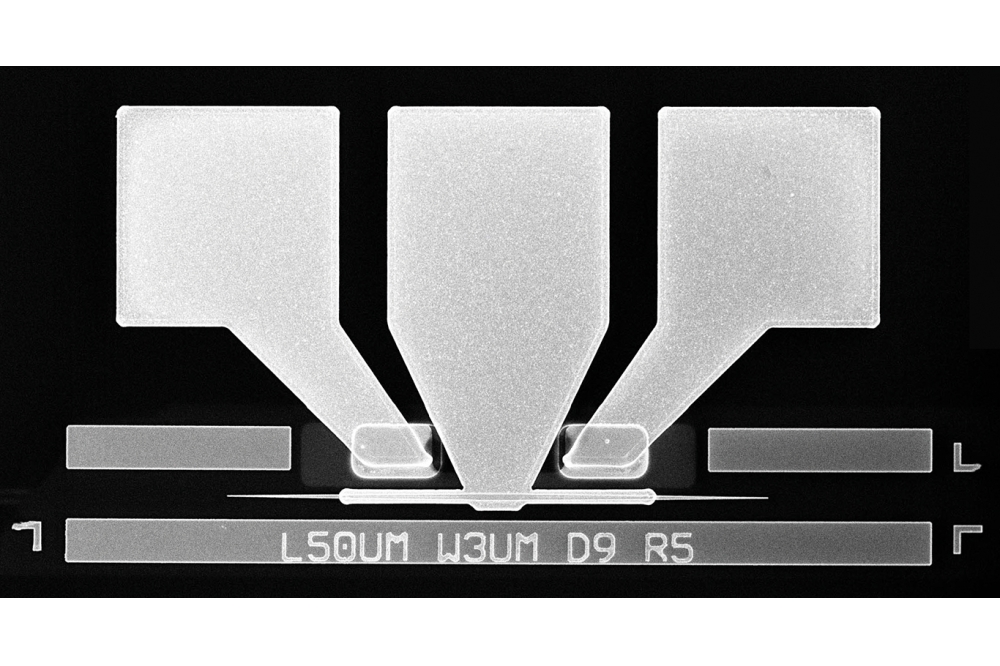

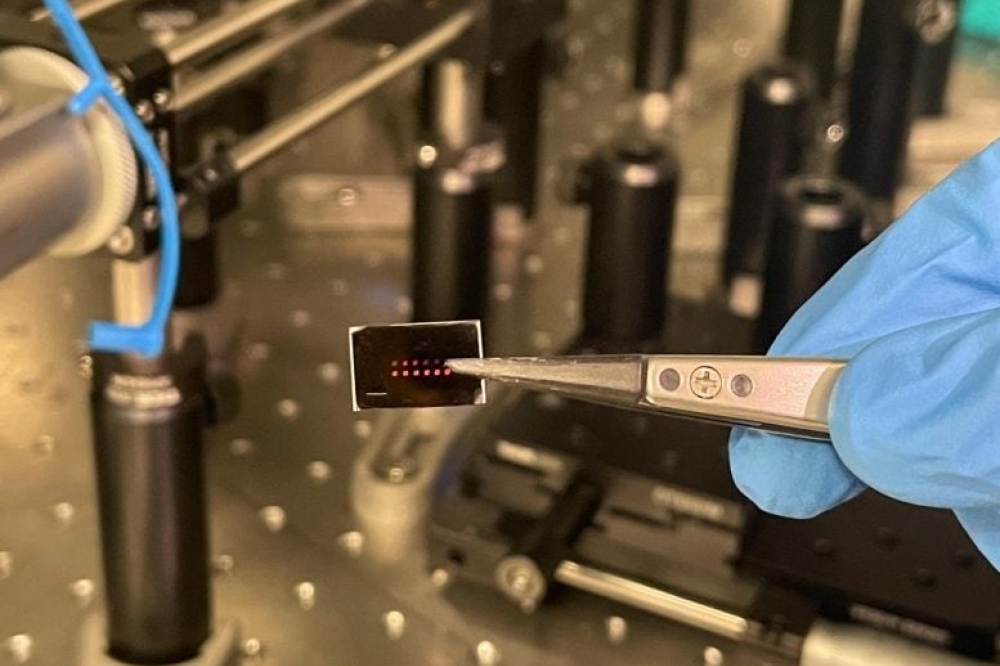

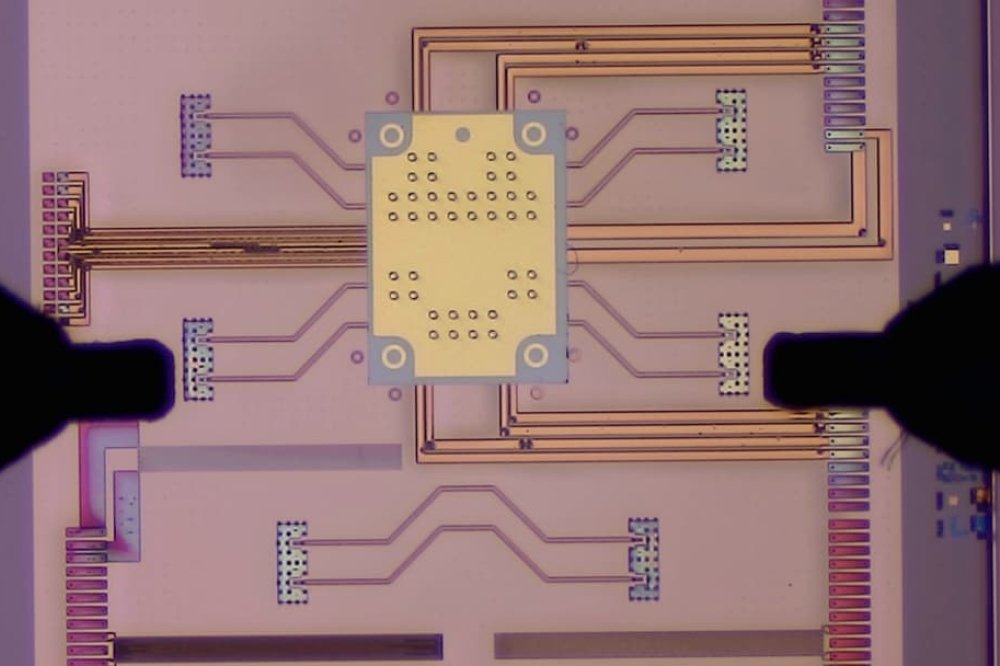

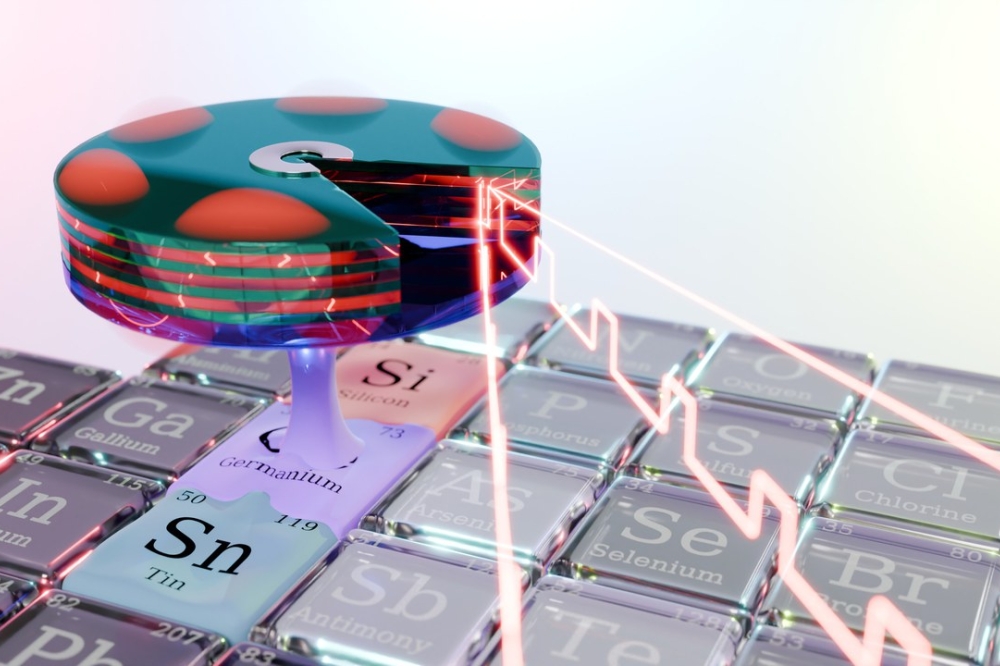

“We developed a technique to use lasers to cool and tightly trap atoms on an integrated nanophotonic circuit, where light propagates in a small photonic ‘wire’ or, more precisely, a waveguide that is more than 200 times thinner than a human hair,” explains Hung, who is also a member of the Purdue Quantum Science and Engineering Institute. “These atoms are ‘frozen’ to negative 459.67 degrees Fahrenheit or merely 0.00002 degrees above the absolute zero temperature and are essentially standing still. At this cold temperature, the atoms can be captured by a ‘tractor beam’ aimed at the photonic waveguide and are placed over it at a distance much shorter than the wavelength of light, around 300 nanometres or roughly the size of a virus. At this distance, the atoms can very efficiently interact with photons confined in the photonic waveguide. Using state-of-the-art nanofabrication instruments in the Birck Nanotechnology Center, we pattern the photonic waveguide in a circular shape at a diameter of around 30 microns (three times smaller than a human hair) to form a so-called microring resonator. Light would circulate within the microring resonator and interact with the trapped atoms.”

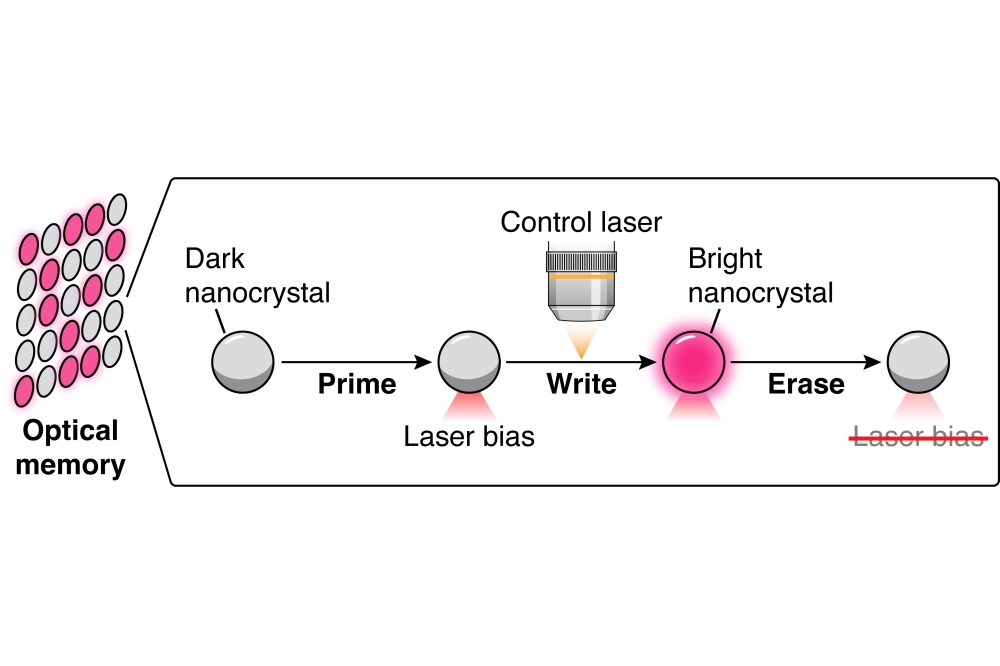

A key aspect the team says they have demonstrated in this research is that this atom-coupled microring resonator serves as a ‘transistor’ for photons. They say they can use these trapped atoms to gate the flow of light through the circuit. If the atoms are in the correct state, photons can transmit through the circuit. Photons are entirely blocked if the atoms are in another state. The more strongly the atoms interact with the photons, the more efficient this gate is.

“We have trapped up to 70 atoms that could collectively couple to photons and gate their transmission on an integrated photonic chip. This has not been realised before,” says Xinchao Zhou, graduate student at Purdue Physics and Astronomy. Zhou is also the recipient of this year’s Bilsand Dissertation Fellowship.

“Our technique, which we detailed in the paper, allows us to very efficiently laser cool many atoms on an integrated photonic circuit. Once many atoms are trapped, they can collectively interact with light propagating on the photonic waveguide,” adds Zhou.

“This is unique for our system because all the atoms are the same and indistinguishable, so they could couple to light in the same way and build up phase coherence, allowing atoms to interact with light collectively with stronger strength. Just imagine a boat moving faster when all rowers row the boat in synchronisation compared with unsynchronised motion. In contrast, solid-state emitters embedded in a photonic circuit are hardly ‘the same’ due to slightly different surroundings influencing each emitter. It is much harder for many solid-state emitters to build up phase coherence and collectively interact with photons like cold atoms. We could use cold atoms trapped on the circuit to study new collective effects,” says Hung.

According to the researchers, the platform demonstrated in this research could provide a photonic link for future distributed quantum computing based on neutral atoms. They also say it could serve as a new experimental platform for studying collective light-matter interactions and for synthesising quantum degenerate trapped gases or ultracold molecules.

“Unlike electronic transistors used in daily life, our atom-coupled integrated photonic circuit obeys the principles of quantum superposition,” explains Hung. “This allows us to manipulate and store quantum information in trapped atoms, which are quantum bits known as qubits. Our circuit may also efficiently transfer stored quantum information into photons that could ‘fly’ through the photonic wire and a fibre network to communicate with other atom-coupled integrated circuits or atom-photon interfaces. Our research demonstrates a potential to build a quantum network based on cold-atom integrated nanophotonic circuits.”

“There are several promising next steps to explore,” continues Hung. “We could arrange the trapped atoms in an organised array along the photonic waveguide. These atoms can collectively couple to the waveguide through constructive interference but cannot radiate photons into the surrounding free space due to destructive interference. We aim to build the first nanophotonic platform to realise the so-called ‘selective radiance’ proposed by theorists in recent years to improve the fidelity of photon storage in a quantum system. We could also try to form new states of quantum matter on an integrated photonic circuit to study few- and many-body physics with atom-photon interactions. We could cool the atoms closer to the absolute zero temperature to reach quantum degeneracy so that the trapped atoms could form a gas of strongly interacting Bose-Einstein condensate. We may also try synthesising cold molecules from the trapped atoms with the enhanced radiative coupling from the microring resonator.”

Image credit: Brian Powell