Ultra-thin 2D materials rotate light polarisation

Researchers say they have achieved a step towards miniaturised optical isolators, which could enable on-chip integration of future quantum optical computing and communication technologies

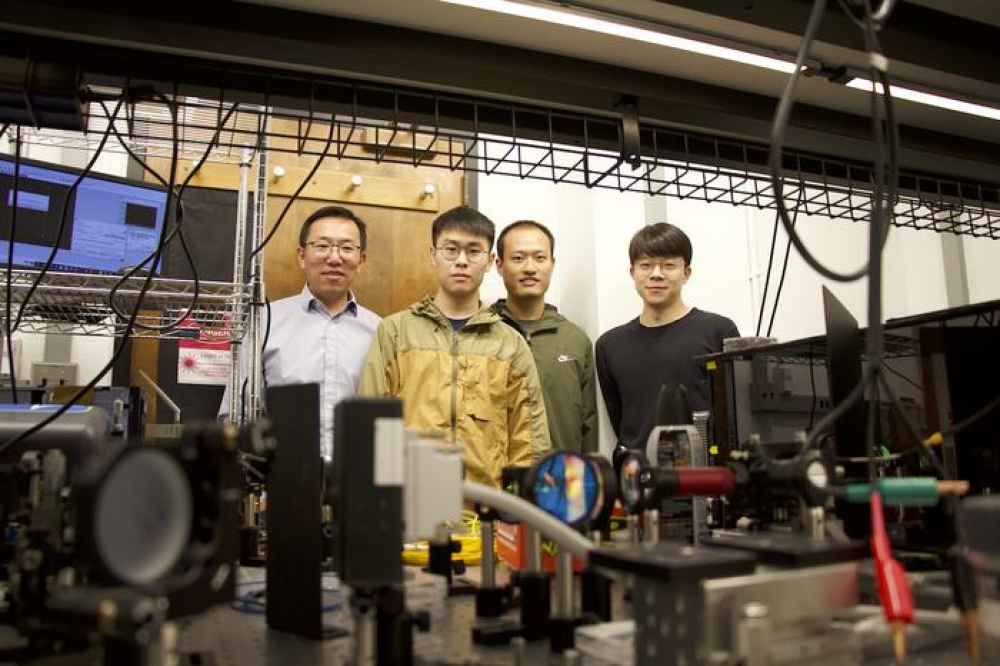

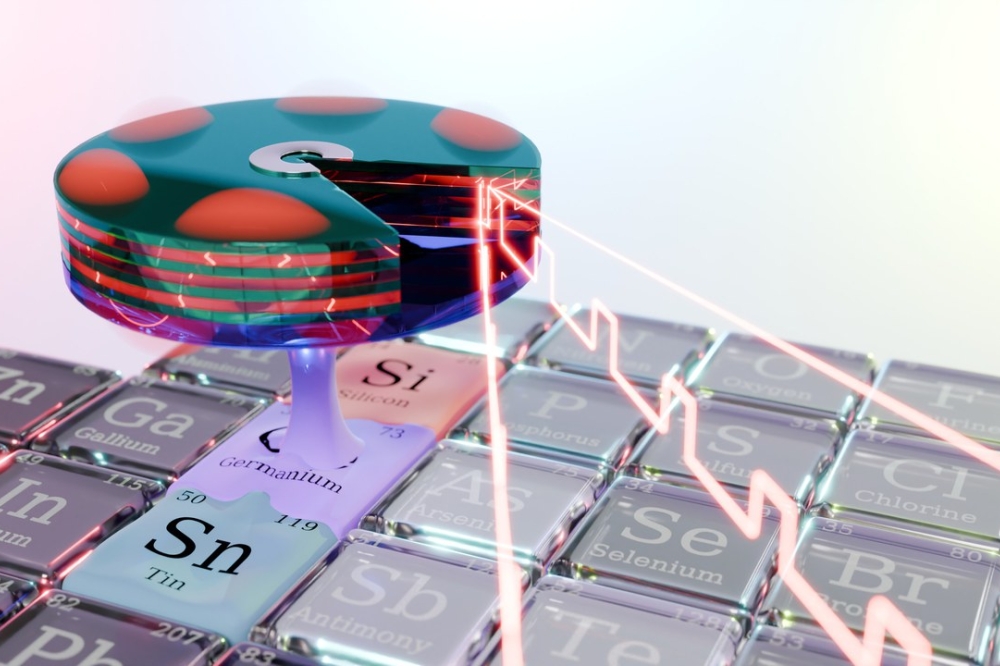

In a new study, physicists have shown that ultra-thin two-dimensional materials such as tungsten diselenide can rotate the polarisation of visible light by several degrees at certain wavelengths under small magnetic fields suitable for use on chips. The team, comprising researchers from the University of Münster in Germany and the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER) in Pune, India, have published their findings in the journal Nature Communications.

It has been known for centuries that light exhibits wave-like behaviour in certain situations, and some materials can rotate the polarisation – the direction of oscillation, of the light wave – when the light passes through the material. This property is utilised in a central component of optical communication networks known as an “optical isolator” or “optical diode,” which allows light with one polarisation to propagate but blocks all light with another polarisation.

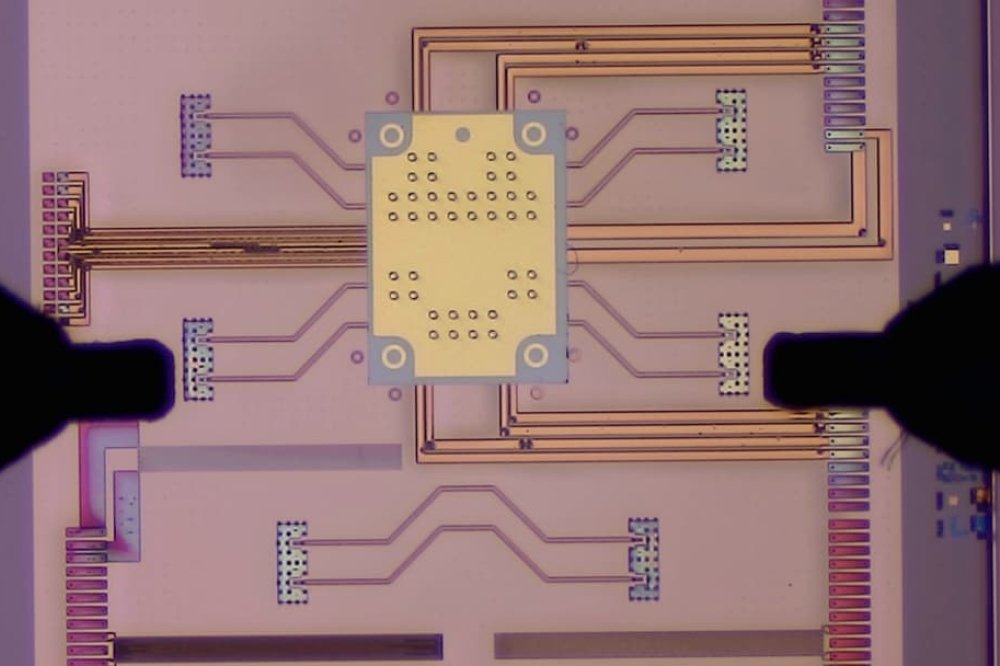

One of the problems with conventional optical isolators is that they are quite large, with sizes ranging from several millimetres to several centimetres. According to the researchers, this means that it has not yet been possible to create miniaturised integrated optical systems on a chip that are comparable to everyday silicon-based electronic technologies. Current integrated optical chips consist of only a few hundred elements on a chip, compared with the many billions of switching elements contained in computer processing chips.

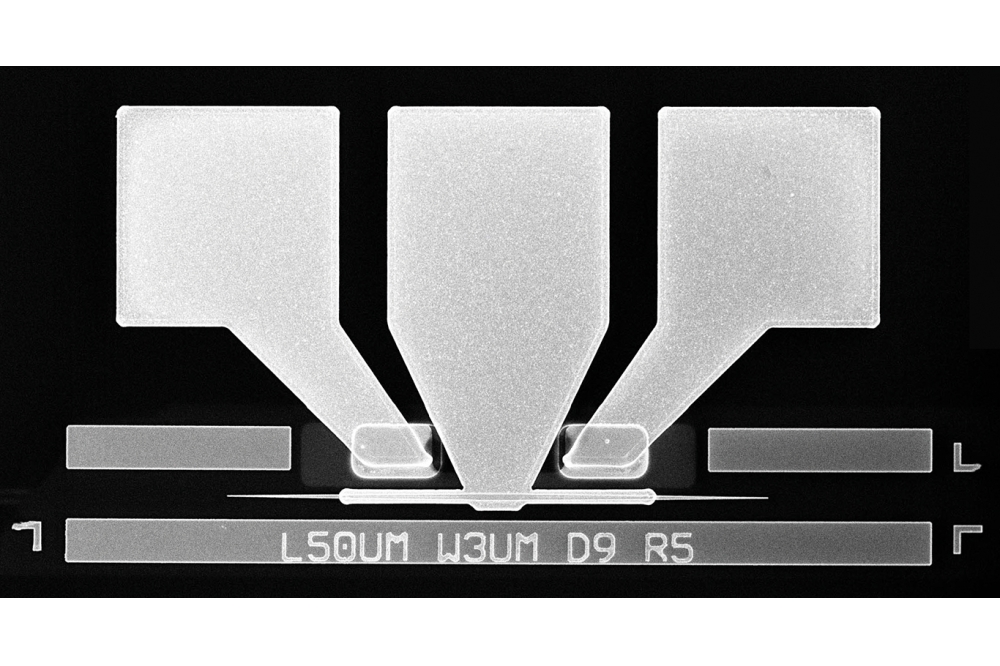

The researchers say that this new development is therefore a step forwards in the development of miniaturised optical isolators. The 2D materials used in the study are only a few atomic layers thick – about 100,000 times thinner than a human hair.

“In the future, two-dimensional materials could become the core of optical isolators and enable on-chip integration for today's optical and future quantum optical computing and communication technologies,” says Rudolf Bratschitsch, a professor at the University of Münster.

Ashish Arora, a professor at IISER, adds: “Even the bulky magnets, which are also required for optical isolators, could be replaced by atomically thin 2-D magnets.” The scientists say this would drastically reduce the size of photonic integrated circuits.

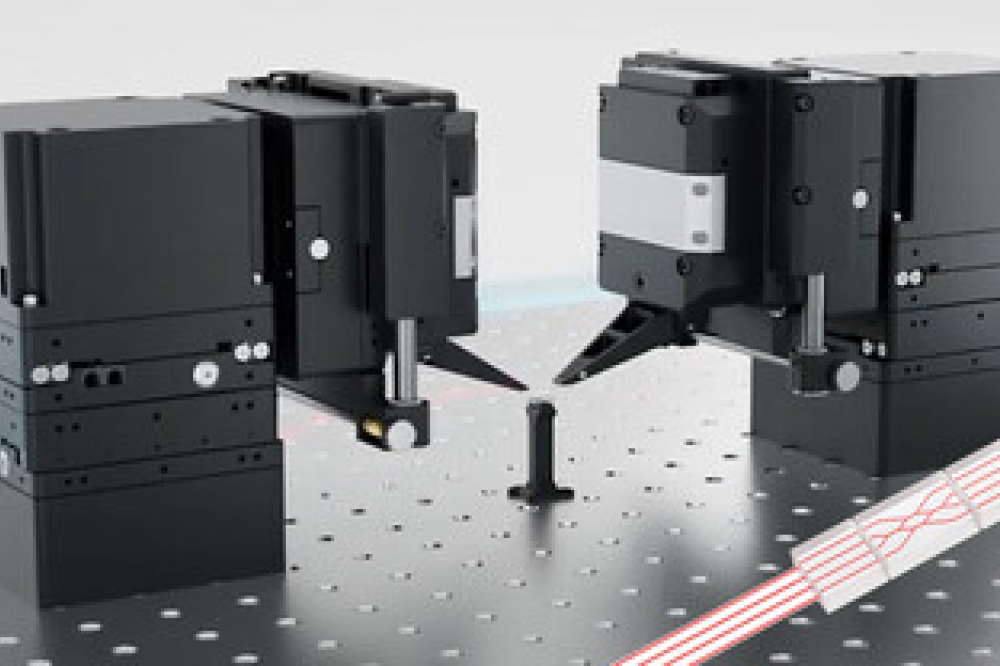

The team discovered that the mechanism behind the effect was that bound electron-hole pairs, so-called excitons, in 2D semiconductors rotate the polarisation of the light very strongly when the ultra-thin material is placed in a small magnetic field. According to Ashish Arora, “conducting such sensitive experiments on two-dimensional materials is not easy because the sample areas are very small.” The scientists therefore had to develop a new measuring technique that is around 1000 times faster than previous methods.

The project is jointly financed by the German Research Foundation (DFG), the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, the Indian technology foundation I-Hub, the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB) of the Indian Ministry of Technology, and the Indian Ministry of Education.