Novel method for making chipscale mode-locked lasers

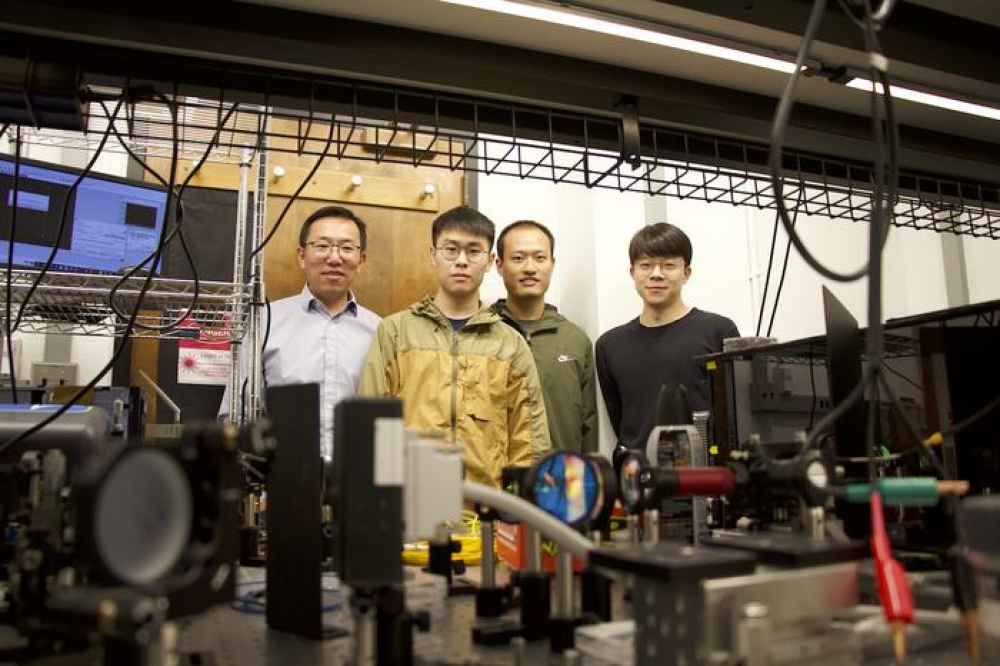

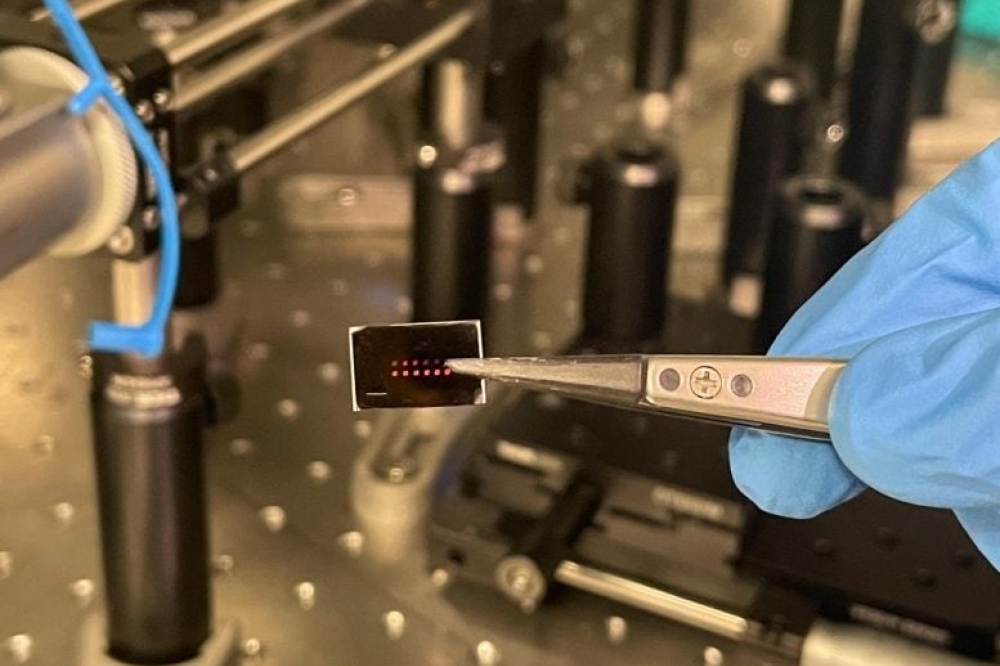

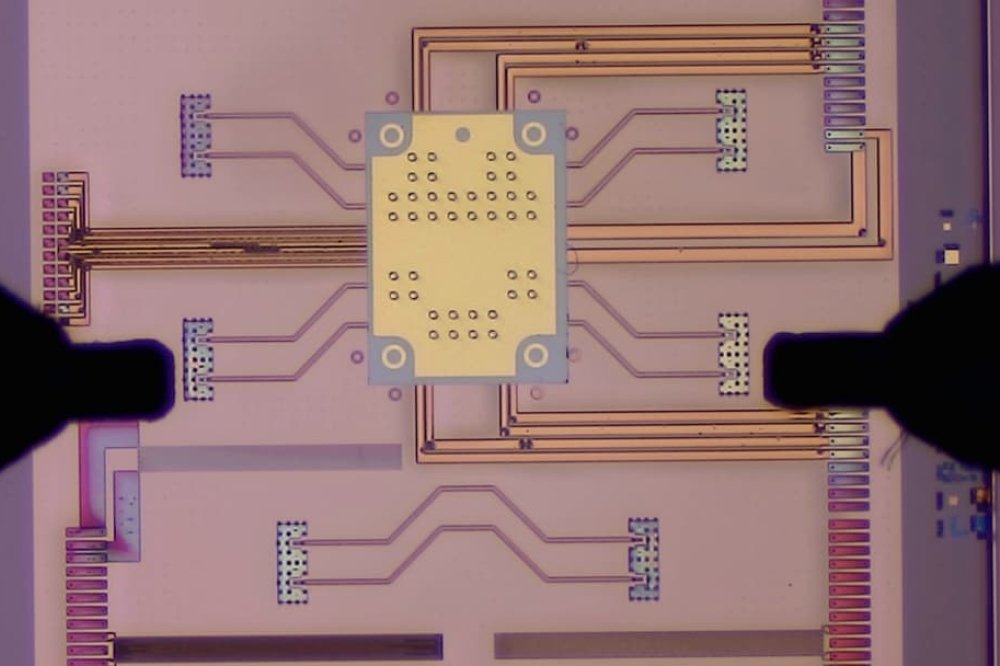

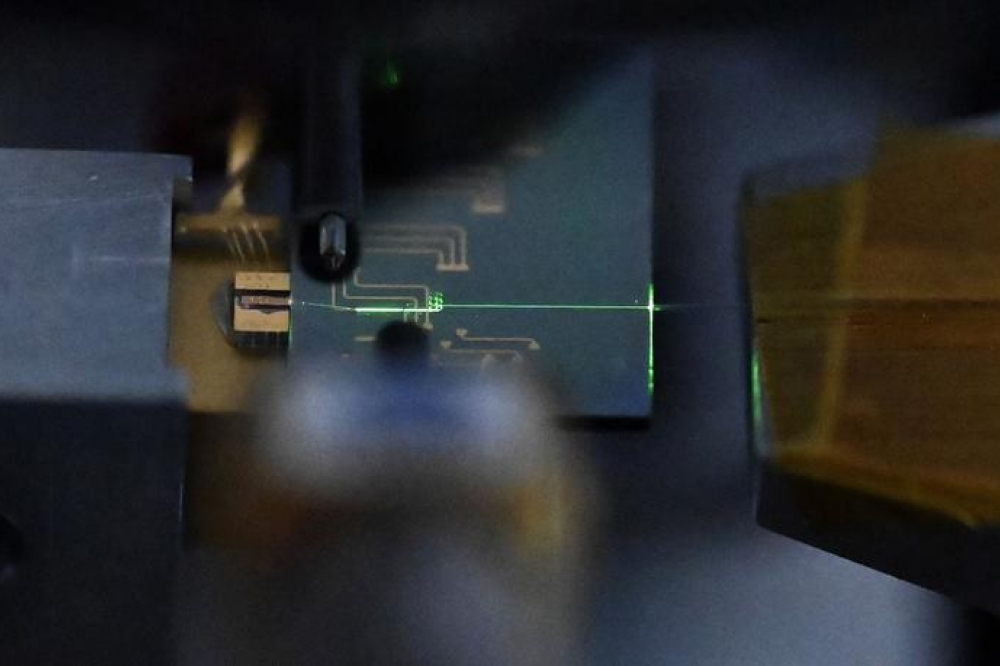

In a paper in the journal Science, researchers have described a new method for making a mode-locked laser on a photonic chip. The lasers are made using nanoscale components, allowing them to be integrated into light-based circuits similar to the electricity-based integrated circuits found in modern electronics. The method was developed by the lab of Alireza Marandi, an assistant professor of electrical engineering and applied physics at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

Mode-locked lasers are lasers that can emit extremely short pulses – on the order of one picosecond or shorter. Using lasers operating on such small timescales, researchers can study physical and chemical phenomena that occur extremely quickly – for example, the making or breaking of molecular bonds in a chemical reaction or the movement of electrons within materials. These ultrashort pulses are also extensively used for imaging applications because they can have extremely large peak intensities but low average power, so they avoid heating or even burning up samples such as biological tissues.

"We're not just interested in making mode-locked lasers more compact," says Marandi. "We are excited about making a well-performing mode-locked laser on a nanophotonic chip and combining it with other components. That's when we can build a complete ultrafast photonic system in an integrated circuit. This will bring the wealth of ultrafast science and technology, currently belonging to metre-scale experiments, to millimetre-scale chips."

Ultrafast lasers of this sort are so important to research, that this year's Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to a trio of scientists for the development of lasers that produce attosecond pulses. Such lasers, however, are currently extremely expensive and bulky, says Marandi, adding that his research is exploring methods to achieve such timescales on chips that can be orders of magnitude cheaper and smaller, with the aim of developing affordable and deployable ultrafast photonic technologies.

"These attosecond experiments are done almost exclusively with ultrafast mode-locked lasers," he says. "And some of them can cost as much as $10 million, with a good chunk of that cost being the mode-locked laser. We are really excited to think about how we can replicate those experiments and functionalities in nanophotonics."

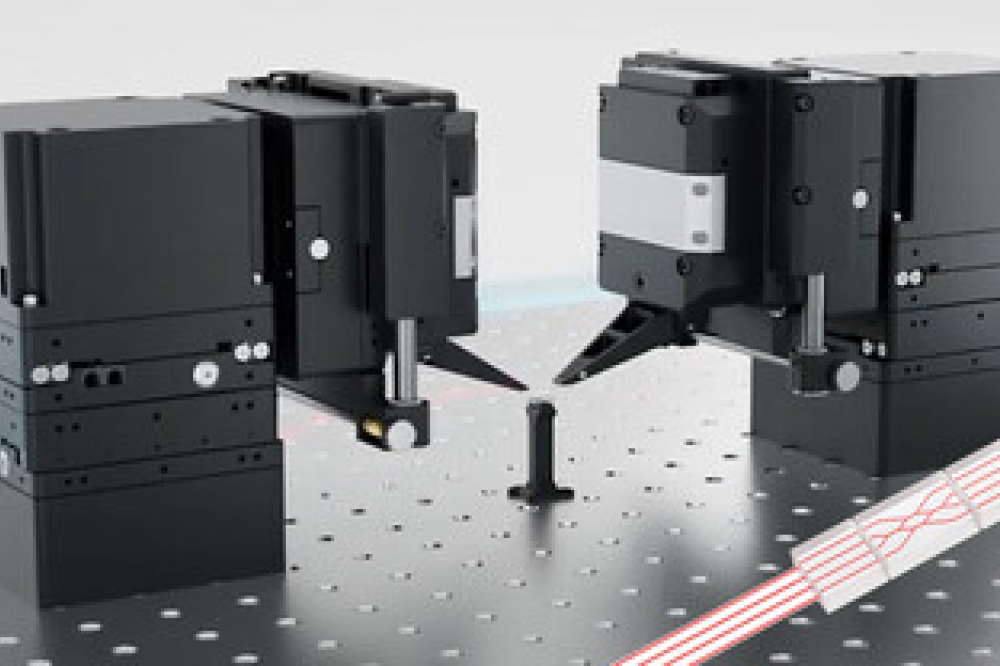

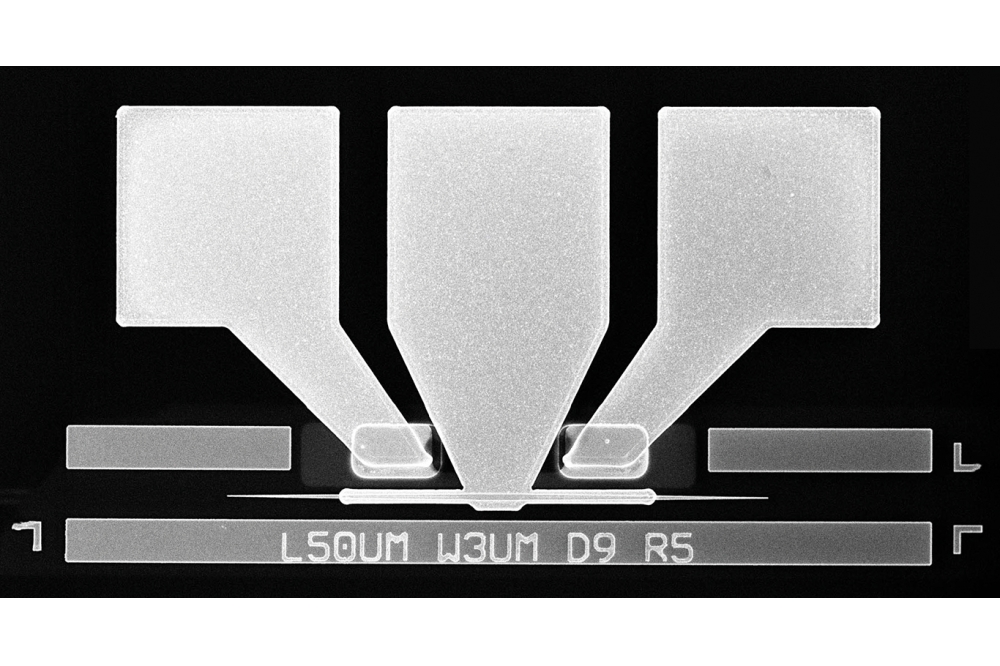

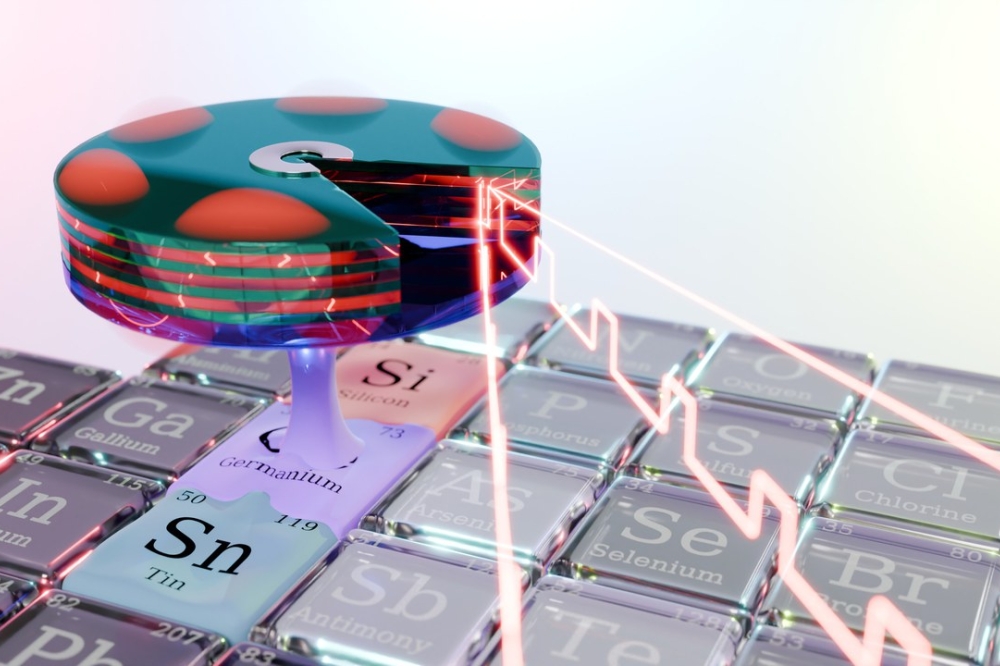

At the heart of the nanophotonic mode-locked laser developed by Marandi's lab is lithium niobate, a synthetic salt with unique optical and electrical properties that, in this case, allows the laser pulses to be controlled and shaped through the application of an external radio-frequency electrical signal. This approach is known as active mode-locking with intracavity phase modulation.

"About 50 years ago, researchers used intracavity phase modulation in tabletop experiments to make mode-locked lasers and decided that it was not a great fit compared to other techniques," says Qiushi Guo, the first author of the paper and a former postdoctoral scholar in Marandi's lab. "But we found it to be a great fit for our integrated platform. Beyond its compact size, our laser also exhibits a range of intriguing properties. For example, we can precisely tune the repetition frequency of the output pulses in a wide range. We can leverage this to develop chipscale stabilised frequency comb sources, which are vital for frequency metrology and precision sensing."