An outlook on the evolution of PICs for future interconnects

Optical transceivers’ capacity has historically grown by 1 dB per year. AI now requires more rapid advances towards 100T or beyond over the next decade. Numerous promising technologies could overcome current bottlenecks.

By Yikai Su, Full Professor in Electrical Engineering, Shanghai Jiao Tong University

In today’s complex global networks, where vast amounts of data must be processed, stored, located, and transmitted, a breakthrough in a single component is not always enough to drive progress at a macroscopic scale. Rather, such advancements can facilitate greater capacity, but only if they can be incorporated into the whole system, and if there are not bottlenecks elsewhere.

Yet there has historically been a mismatch in the growth rates of computational and data transmission technologies. The speed of computing hardware such as CPUs and GPUs has increased at an exponential annual growth rate of 73.8 percent, or 2.4 dB per year. Meanwhile, the interconnect technologies, both electrical and optical, have lagged behind; over the past decade or so, the data rates for electrical connects between electronic chips grew at 0.73 dB per year [1], while optical interconnects improved modestly more quickly at 1 dB per year [2].

Now, the emergence and rapid proliferation of AI applications has tremendously boosted demand for higher data capacities to an unprecedented rate of approximately 10 dB per year [3]. This number has two implications. First, more computing racks and clusters are needed to compensate for the gap between the required AI datacentre capacity growth (10 dB per year) and computing hardware development (2.4 dB per year). This has led datacentres to explore scale-up and scale-out approaches.

Figure 1. Predicted capacity growth for PICs. The current year of 2025 starts with 1.6T for optical transceiver modules in production, while lab prototypes have demonstrated 4T PICs. Using the annual growth rate of 1 dB per year for optical modules based on historical data, the PIC capacities for products and lab demonstrations will very likely to increase to at least 16T and 40T, respectively, in 10 years. New technologies are expected to speed up the process driven by the recent emergence of AI with R&D funding support from industry and academia.

The second result is that the industry urgently needs significant innovations in interconnect technologies to keep up with the advances in computing hardware and overall AI datacentre expansion. Even with optical interconnects, the gain of 1 dB per year for a module is much slower than that of computing electronics, and may eventually become a bottleneck in AI clusters.

We can estimate a baseline for the future capacity growth of optical interconnects, assuming that future development is unlikely to be slower than the past rate of 1 dB per year. Figure 1 shows this lower bound for the projected capacity growth of interconnect PICs, starting at 1.6T for existing products [3], and at 4T for chips demonstrated in research labs [4]. Following the trend, the capacities rise to 16T for commercial products and 40T for lab advancements in the next 10 years. These predictions offer bottom-line targets, because new technologies are likely to appear and considerably accelerate progress in R&D and commercialisation.

On the other hand, we can also calculate an aspirational target for the development of optical interconnects in a hypothetical scenario where it keeps up with computing electronics. This high rate of 73.8 percent (2.4 dB per year) is ambitious but may not be impossible for PICs to achieve. Looking inside a CPU or GPU, the clock rate has remained almost the same for years, but computing power has continued to grow, thanks to the massively parallel processing of data streams. Optical interconnects may take a similar technological path, with massively parallel channels integrated on a PIC. If optical input/output were to catch up and keep pace with the development of computing and switching chips, the extrapolated capacities would reach unprecedented levels of 100T or even achieve rates on the order of Petabits per second (Pbps), as Figure 2 illustrates.

Figure 2. The projected upper bound capacities are calculated assuming

technological breakthroughs in photonics enable the same rate of growth

as that of computing hardware (GPUs, CPUs), which may be feasible

through dense integration of massively parallel channels on a PIC.

However 100T or Pbps-class PICs will encounter significant challenges

and some fundamental limitations.

The goal of realising a 100T-class PIC or beyond presents significant challenges for incumbent technologies, as some of them may come up against theoretical limits. Silicon modulators based on the carrier dispersion effect, for example, have a theoretical maximum bandwidth of approximately 100 GHz. Even using Nyquist shaping and PAM-4 to increase data rates, the modulator’s single-polarisation limit may be 400G.

Required performances and associated challenges

The single-channel data rate for current PICs is 100G, and engineers are targeting 200G and beyond for next-generation PICs. If we take 256G as the raw data rate for a single channel, we would need a total of 4096 channels to accommodate 1 Pbps. Even with a dense channel spacing of 50 GHz, one waveband cannot support the required capacity for this goal. Designs will therefore need multiple fibres and multi-wavelength channels. Specifically, we can calculate that 64 fibres and 32 wavelengths would be required [5].

Bandwidth scaling of electronics can help to increase the single-channel data rate and thus reduce the number of channels. However, this is likely to happen at a slower pace than the rising demand for data, due to intrinsic limitations set by materials and device operation principles. Even with huge strides in the single-channel data rate approaching 1T, 1000 channels would still be needed to achieve the Pbps capacity. It is therefore likely that dense integration of massively parallel channels will be essential.

Each channel typically consists of a laser source, a modulation device, a (de)multiplexer, a photo detector (PD), and analogue electronics. Practically implementing such a high channel count on a large-capacity PIC poses many engineering challenges, including accommodating high integration density while avoiding crosstalk and maintaining high yield, as well as developing feasible high-speed dense packaging.

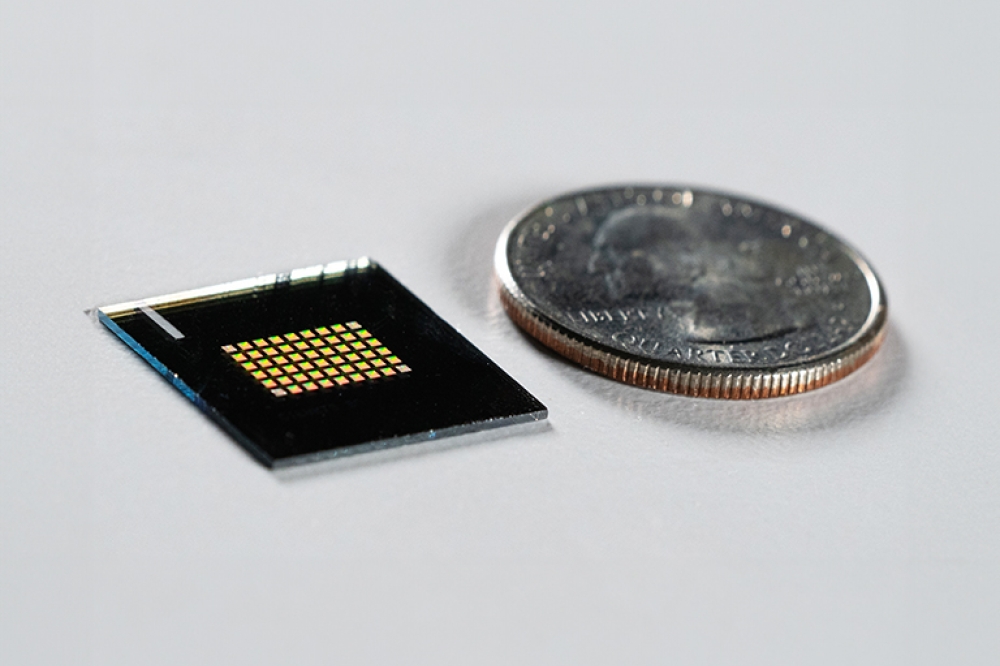

Summing up the footprints of these components, the minimum chip size is 462 mm2 [5], and the resulting bandwidth density is 2.16T per mm2. However, this calculation allowed for no margin, so the practical chip size would be much larger than the ideal case. This large footprint presents fabrication issues, such as uniformity across the wafer and stitching errors, as well as the problem of higher propagation loss on a wafer-scale chip.

Another challenge lies in the chip’s power efficiency and total power consumption. Assuming the modulators, PDs, and peripheral analogue electronics each consume 100 fJ per bit, the power consumption is 300 W for these components. By adding 192 W power from the distributed-feedback Bragg-grating (DFB) laser array, the total power consumption for a PIC is 592 W, which may exceed the capability of conventional thermal management systems.

Table 1 summarises the required performances for a 1 Pbps PIC and the associated challenges [5]. There are three major bottlenecks: integration and packaging of massively parallel channels on the order of thousands; a large, potentially wafer-scale PIC footprint; and high power consumption of a few hundred watts, requiring active components to have ultra-high power efficiencies better than 100 fJ per bit. The parameters listed in the table are close to the ideal cases calculated from the best reported or projected results. Real implementations may face significant engineering challenges to achieve unprecedented performances while simultaneously ensuring that the Pbps PIC is functional under practical conditions.

Table 1. Top-line requirements for a 1 Pbps PIC and the associated challenges.

Breakthroughs to overcome bottlenecks

While the challenges outlined in Table 1 currently present significant obstacles to achieving Pbps-class PICs, they also offer opportunities for huge performance improvements, should they be overcome. The expanding field of PIC research across a wide range of optical components offers numerous routes to potential breakthroughs.

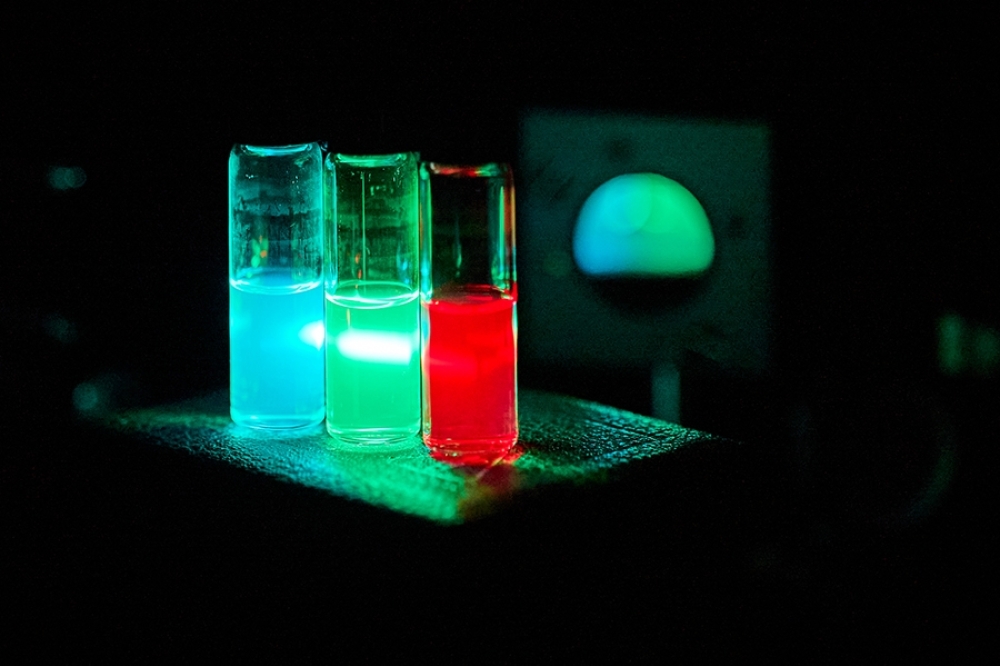

Since lasers account for a large portion of the footprint and power consumption of PICs, progress in laser integration may significantly improve PIC performance. A conventional DFB laser with power split may provide 8-16 channel outputs, but multi-wavelength lasers could allow for more. Various types of comb lasers have attracted tremendous interest in academia, including silicon nitride frequency combs and quantum dot (QD) mode locked lasers (MLLs), among others.

Comb lasers can substantially reduce insertion losses originating from fibre coupling and packaging. Due to the large number of wavelengths they generate, comb lasers offer advantages in terms of compactness and integration density. In particular, III-V QD MLLs exhibit high efficiencies with inherent defect and temperature insensitivity. Silicon nitride frequency combs also provide multi-wavelength outputs based on Kerr nonlinearity and dispersion management. Both schemes offer broadband multi-wavelength outputs, reduced footprints, and reduced number of lasers employed. For large-scale integration, however, additional on-chip optical amplification of the laser output may be required.

Advanced modulators are another component with potential to overcome current performance barriers. Conventional Mach-Zehnder silicon modulators occupy large footprints due to the weak electro-optic (EO) effect based on carrier induced dispersion. Resonator modulators, such as micro-ring resonators (MRR), Bragg gratings, and nanobeam resonators, can significantly shrink the footprints. Higher-speed ultra-compact modulators will be key to reducing the number of channels and the PIC footprint.

Figure 3. A conceptual illustration of possible techniques integrated on a PIC. In the transmitter component, power splitting and wavelength demultiplexing may be employed to construct thousands of data channels. Ultra-compact and high-speed modulators modulate the data on the optical carriers. At the receiver side, IQ DD receivers may double the capacity. 2.5D or 3D co-integration of electronics can be implemented with the PIC (not shown in the figure). High channel number, footprint and power consumption will be the bottlenecks to overcome.

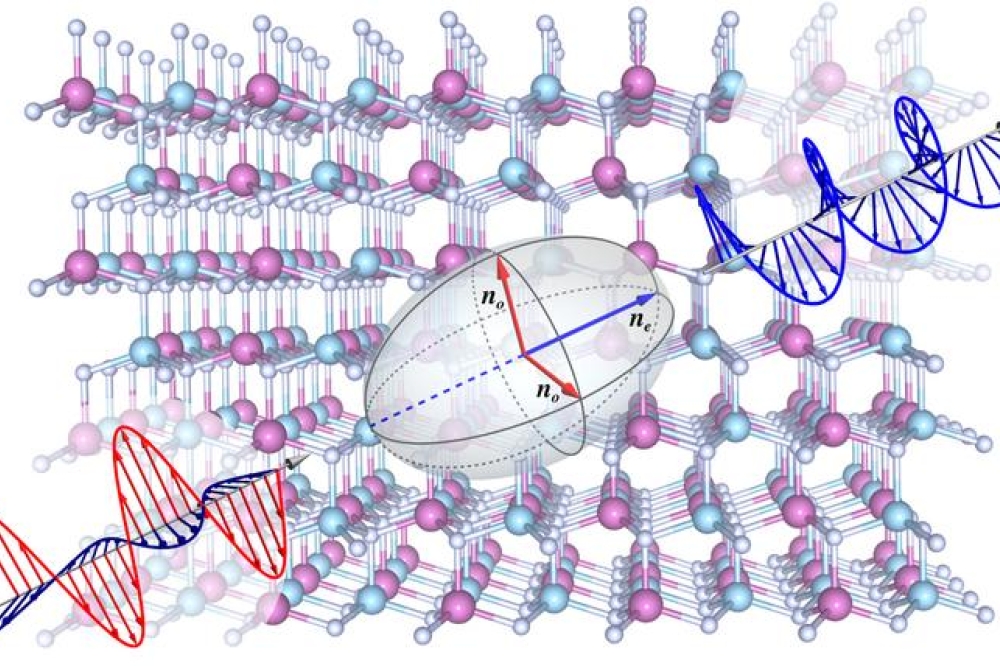

As previously mentioned, silicon modulators may approach their bandwidth limit, but new EO materials with high EO coefficients are emerging for heterogeneous integration, such as ferroelectric materials including lithium niobate and barium titanate, and high-reliability EO polymer materials. Other desirable features for next-generation modulators include intensity/quadrature (IQ) modulation, athermal operation, driver-less or capacitive-driven modulation, high process tolerance, and ultra-low power consumption heaters.

Improvements in MUX/DEMUX devices could also offer an opportunity for progress. Arrayed waveguide gratings (AWG) and cascaded MRRs are two devices typically used for wavelength (de)multiplexing. MRRs have a larger footprint relative to AWGs if the channel count is high. Innovations in this area may include sub-wavelength engineering and inverse design. Currently it is still challenging to simultaneously optimise characteristics including loss, passband, crosstalk, channel number, and fabrication-error tolerance. Technological advances are needed in terms of design and fabrication methodologies.

When it comes to photodetectors and receivers, speed and efficiency are two key factors to consider. New materials may be explored, with one exciting area of development being the co-integration of PDs and electronic amplifiers using 2.5D or 3D integration techniques, allowing for reduced footprints and power consumptions. Another research direction focuses on improving the electrical spectral efficiency and thus the data rate of a direct detection receiver close to that of a coherent receiver by using full-field recovery technology – directly detecting the phase component of a complex signal in addition to its amplitude information without the need for coherent detection. In this case, optimised filters are crucial in the receiver design.

Finally, high-density packaging and thermal management on a PIC with thousands of high-speed electric contacts is a focus area with promising approaches for progress. By using nanophotonic interposers and automated assembly techniques with nanometre-level precision, for example, researchers can improve packaging efficiency and alignment accuracy. On the thermal management side, advanced cooling solutions such as microfluidic cooling through microfluidic channels, can manage heat effectively.

Figure 3 illustrates a vision of how some of the techniques described above might be integrated on a PIC. These are just some of the research areas that could unlock the next step change in performance in integrated photonics. New innovations will always arise, and it is possible that advancements other than those outlined here may change the path of PIC development, overcoming bottlenecks and accelerating the realisation of Pbps-level PICs.